MMORPG Devlog 1: Building an MMORPG in Unity Because I Can

This post is part of my MMORPG Devlog series.

This post is part of my MMORPG Devlog series.

I’ve been fascinated by the idea of developing games since I first started teaching myself to program around the age of ten. Of course, way back in the early 2000s, we didn’t have the wealth of freely-available game engines with fancy rapid prototyping. Big names like Unreal or idtech3 cost a lot of money, and you were almost certainly going to have to be familiar with C++ to hack even simple things together. That’s a tall order for a kid, especially when you’re more familiar with the likes of PHP and JavaScript (yuck). So I didn’t really get into game development back then (though I have played around a little with Unity in recent years), but I did read about the topic quite a bit.

One thing stuck with me, as I read forums or the limited books that I could get my hands on through interlibrary loans: everyone always laid on thick that MMORPGs, which were the hottest genre at the time, were “too complicated” for the hobbyist. Obviously, that wasn’t something you wanted to hear when you were spending too many hours playing RuneScape and frequently read about EverQuest and World of Warcraft.

They did make a reasonable point. An MMORPG is a massive undertaking for a beginner, since it involves a reasonable knowledge of many deep topics, such as networking, concurrency and databases. The thing is…that doesn’t preclude the possibility of a sufficiently knowledgeable hobbyist pulling it off. In fact, Ultima Online was initially produced by a team of 4-5 people and the original incarnation of RuneScape was the work of two brothers.

So, I decided “why not?” I’m on my third year of a Computer Science degree; I can do this. I had some free time while self-isolating before university classes started back up, so I started planning out a hobby MMORPG.

I figured it would be a fun thing to play with over time. Probably a very long time. Maybe it’ll be an actual live game someday, or maybe I’ll get bored and dump the source on GitHub down the line. Either way, it’ll be an interesting project whenever I have some time.

Without further ado, here are some highlights from the first month of development.

Networking Scaffold

The first few days were mostly spent on networking. I immediately rejected any of the high-level tools that involve running Unity on the server, planning from the start to have a custom dedicated server. I fired up a test project and spent some time experimenting with raw C# sockets, until I had the basic concepts down, but ultimately decided to use a lightweight framework to simplify some things.

LiteNetLib, the library I chose, uses UDP but has support for TCP-style reliable/ordered packets and takes the pain out of serialization. You get a lot of features for free, but it just does networking. Nothing fancy or inherently game related. Its NetPacketProcessor class handles routing, so you can easily define methods to invoke when packets come in, and the serialization tools allow you to define packets as plain classes.

Once I had that figured out, I started scaffolding the server out, then created my MMORPG project in Unity and wrote some scripts to connect to the server.

Authentication

This one is something you won’t see game-related things online talk about, but it’s very important. You need to have a way for users to log in, and you need to do so in a way that does not expose their passwords. Not only do you need to have hashing for the passwords, instead of storing them in plaintext, but you also need encryption while the password is in transit.

For hashing, .NET Core includes functions that do the job. The overall process works the same as any Web application: hash the password and store it in the database when the user registers, then on log in attempts you hash the password submitted and see if it matches.

But that’s not really enough. We don’t want to risk someone sniffing packets and hijacking users’ accounts, do we? The contents of sensitive packets, such as the authentication packet, need to be encrypted in flight. Some games encrypt everything, others don’t. LiteNetLib has already made the opinionated decision to not use encryption, which means you have to encrypt the data before building the packet, as opposed to having the socket’s transport taking care of it.

Fortunately, .NET Core also has RSA encryption in its standard library. If you’re not familiar with public-key encryption, not to worry. Unlike hashes, which only work one-way, RSA is symmetric. Each party has two keys, one public and one private. If you have someone’s public key, you can use it in tandem with your private key to produce a message that cannot be read by anyone who lacks the other half of the recipient’s key-pair. So the process the game uses follows this workflow:

-

When the server starts up, it generates its private and public key.

-

When a client wants to connect, the client opens a socket connection to the server and sends a packet asking to authenticate.

-

The server sends back a packet containing its public key.

-

The client takes the private key it generates and uses it with the server’s public key to encrypt the username and password to be sent.

-

The server uses its private key to decrypt the incoming message.

-

The server queries the database for a row matching the username, hashes the password in the login attempt, and checks to see if the two hashes matched. If they do, a success message is sent back…otherwise the client is kicked.

Git!

Right around now, I started having that nagging feeling that I had gone far too long without an off-site backup. I had already been using Git locally since the beginning, obviously, but I really needed to be able to push it to a remote repo and make sure I had more than the copy on my laptop.

How to Git with Unity tells you everything you need to know about making Unity play nicely with Git. It gives you some configurations that make sure data is serialized in plain text instead of binary, so your changes can be tracked, as well as LFS details and a .gitignore. Git LFS helps Git deal with the large assets that games may have.

Since GitHub’s LFS offerings cost a bit, and I already have a server, I installed Gitea. It has the core features you’d expect from a GitHub alternative, and you can choose to either store LFS objects locally or to outsource them to Amazon S3. My VPS’s SSD space is bigger than I’m likely to need, but it’s nice to have that option.

Database

With an authentication system working, albeit with a hard-coded test username and password, the next logical step was to create a database that would hold the user account information…and a separate one for the game world. By having them split, it would make it easier to support multiple servers down the line.

Not being terribly familiar with the C# ecosystem, I had to do a bit of searching before settling on a plan for the database. I knew I wanted an ORM of some kind, since I’d eventually have many different sorts of data to persist. I also wanted to, ideally, use SQLite for easier development and be able to later switch over to MySQL or PostgreSQL for production.

I briefly looked at the Dapper micro-ORM, but settled on Microsoft’s own Entity Framework Core, because I wanted migrations and other things it comes with. Whether that decision will work out or not is a question for the future, but so far it seems to work just fine.

The running theme seems to be that the server does a lot of the same things as a large Web application. You model data, shuffle it to and from a database, and talk with clients over an API. The only difference is you’re using an open UDP socket with purpose-built packets instead of something like REST over HTTP.

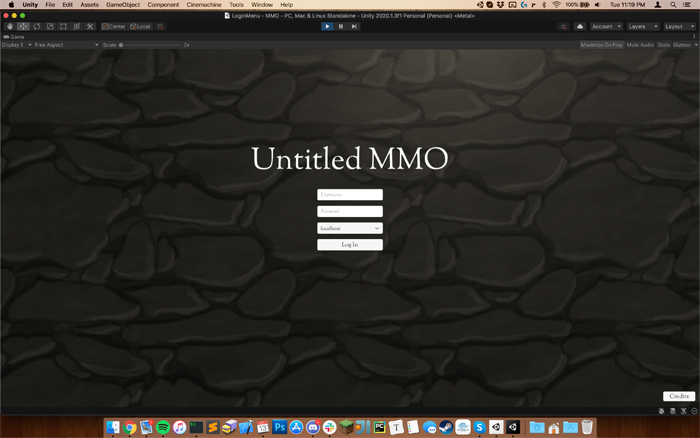

Login Menu and Character Selection

Now it’s time to do some work on the client. When you start the game, the first Scene loaded by Unity is the Login Menu. Attempting to join the game fires off the packet exchange detailed above in the Authentication section.

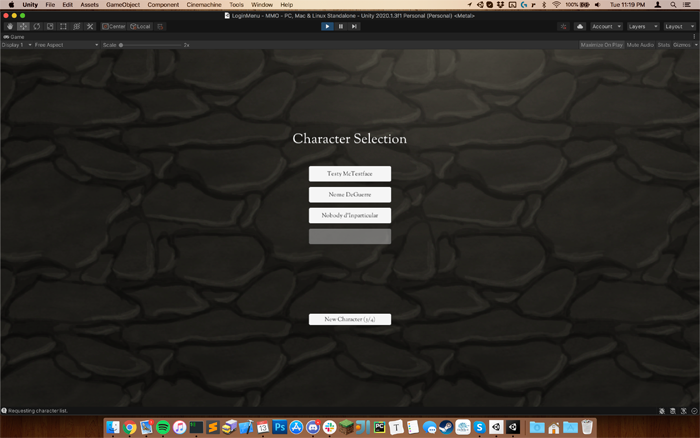

Upon successful authentication, the server dispatches a packet with a list of the user’s characters. When it’s received by the client, the menu changes to show a list of characters to choose. Currently there is no way to add a character other than editing the database, since that will probably involve having more of an idea how character customization might work…

When a player is selected, a packet is sent to the server to join the game, and the server responds by sending a player spawn packet. This commands the client to load a Scene by name, including the coordinates and rotation.

Zone Architecture

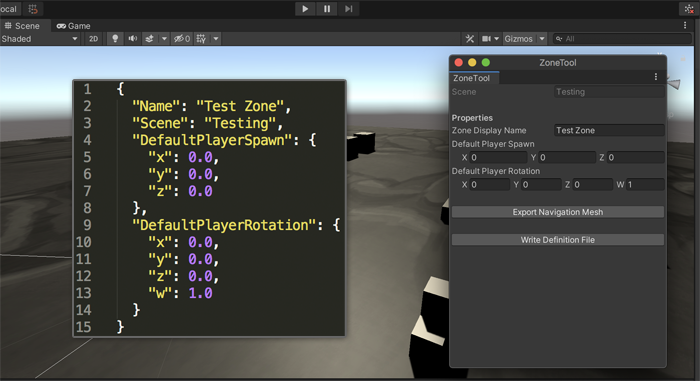

Zones are a server-side concept that section off parts of the world. Each zone has a Unity Scene associated with it, a list of players in the zone, a list of entities (mobs and NPCs, eventually), and other data. Each zone is defined by a JSON file that contains the relevant information.

Every time the server loop ticks (a fixed number of times per second), it calls each zone’s Update() method, which is responsible for updating all or some of the entities contained within. So it might run mob behaviors near players or do nothing at all if the zone is empty. Every n ticks, player data (e.g. location) will also be persisted to the database.

I developed an editor tool that will automatically generate zone definition files based on input configuration. It’s just the absolute basics right now, but eventually it will be expanded as new features are implemented. For example, exits to other zones may be defined with boundaries in-editor, and the zone definition tool will serialize those as well. NPC spawn points will also be marked in a similar fashion.

The zone tool also has a utility that extracts the vertices and triangles from Unity’s navmesh and writes it out to an OBJ file that can also be copied to the server. This is how mobs and NPCs will be able to pathfind, since that has to be done server-side. It could also be used to check if ranged abilities are obstructed by walls.

The base Zone class is also meant to be inheritable, to support special Zones with procedurally generated content. This factors greatly into the premise I’ve been kicking around for the game.

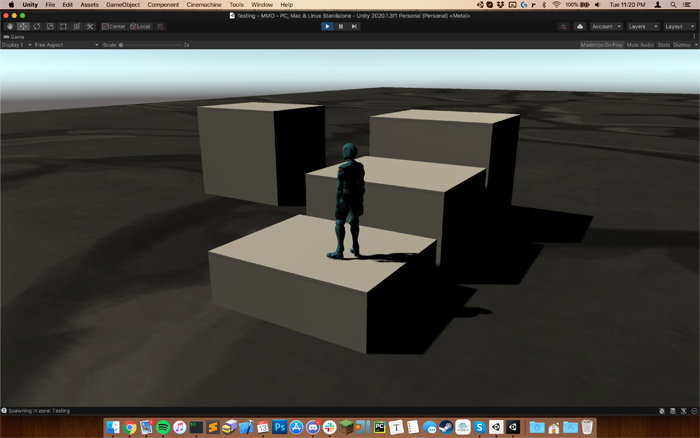

Player Spawning and Controller

So far, the spawn packet works as expected, using information stored in the database. However, I have not yet fully implemented the logic to handle movement requests from the connected clients. The player can walk around using a basic third person controller, but nothing is sent to the server. I have it planned out on paper, but haven’t finished programming it.

The basic idea for movement is for the client to send updates, multiple times per second, of where the client is moving to. The Euclidean distance between the two points can then be checked to ensure that the player is not moving too far between update intervals. If the delta is greater than the cutoff, the location is reset, and the client will “rubberband” back. This (relatively simple) method is commonly used for games where player movement isn’t a gamebreaking issue, as far as cheating goes. (Minecraft and World of Warcraft operate similarly.)

The method that is increasingly common in fast-faced games, like First Person Shooters, is for the client to send a unit vector of the player’s input to the server, which then calculates the movement update (multiplying the vector by the time difference and legal movement speed) and then commands the client to move the player. Since this is very latency sensitive, they interpolate and predict what the server would do so it looks less stuttery when ping time is reasonably low. (But a little lag still throws it all off.) This is a lot more complicated, and definitely worth it for some games, but overkill for something like this.

With either method, the server is the source of truth and has the final say.

For testing purposes, I’m using a model from Adobe Mixamo with some of the included animations. I’m also using a basic movement controller that allows for jumping, and the Cinemachine package is handling camera movement. This will all replaced/tweaked over time, but I needed something to start with while working on the more interesting parts.

Conclusion

Everything is very iterative, and the project definitely does have a huge scope. It should keep me busy and scratch the recurring itch to make Minecraft server plugins. Why hack together mods for someone else’s game when you can make your own? I have a notebook slowly filling with plans for facets of the system, sketches of zones and a rough premise. It’ll be fun to slowly realize that vision.

I will probably post sporadic updates when I do something new and interesting.