MMORPG Devlog 3: Chat and Commands

This post is part of my MMORPG Devlog series.

One of the most important parts of an MMORPG is chat. Being able to interact with other players is a a staple feature of the genre, and it’s essential to have any sort of community aspect. As far back as MUDs, the ancestor of the modern MMORPG, just hanging out and talking to people has been a core part of the online role playing game experience. A chat system also serves as a means of command input, which is useful for functionality that doesn’t need its own GUI…or moderation tools.

Network Packets

I went back and forth quite a bit with my initial planning for the networking side of the chat system. I initially wanted to combine the system backing the garden variety chat pane with the structure that would eventually be required for things like NPC dialogue, which would require a more flexible schema to accommodate various metadata values in addition to the body text. In the end, I realized that was really best left as a separate concern and decided that command and response packets should be kept simple for now.

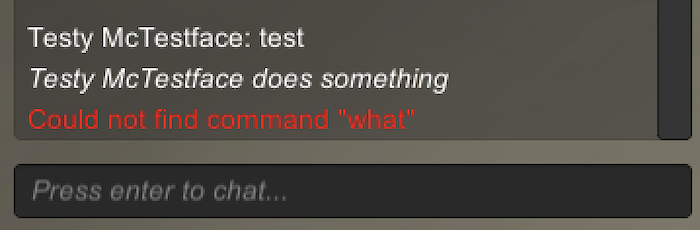

The scheme I arrived at is akin to RPC. The server treats anything coming in from the client as a command, dispatching it to the appropriate class in the command manager and delegating any further responsibility to the corresponding command class. The server can, at any time, send a chat packet to a client and the contents will be rendered in its chat lane. When the user types a message into the chat input and does not prefix it with a slash character and command name, the client assumes they’re just chatting to players in the zone and prefixes the message with /say. The (LiteNetLib) packet classes backing this are basically just wrapping a single string value.

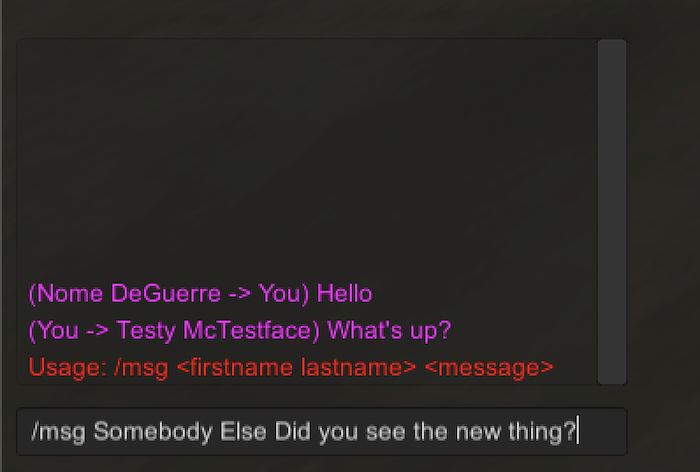

Chat packets can contain Unity rich text markup, allowing the server to colorize text or use bold and italic type. Incoming commands are run through a basic sanitizing routine to make sure a player cannot insert the tags for nefarious reasons. (It’s just a simple, but thorough, regex since the syntax is far more limited than something like HTML.)

Designing the UI

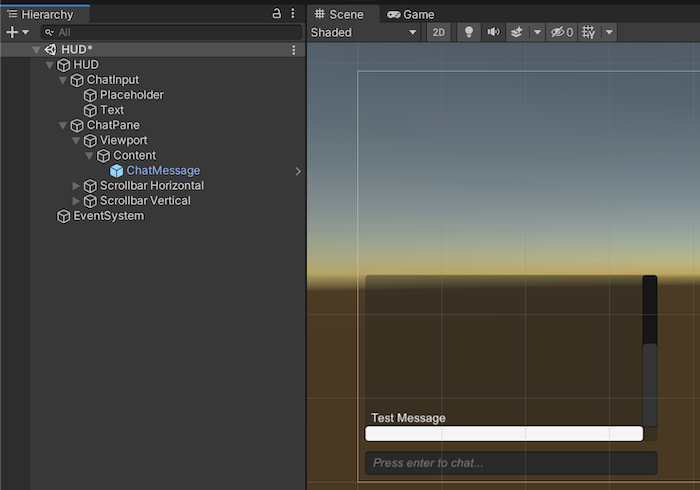

The chat pane is made of two basic Unity UI elements: a text input field and a scroll view, each with a small script component to add the desired behavior. The text input is the simplest, listening for presses of the return key and focusing/unfocusing the field programmatically. This hooks into the character controller to freeze player movement while the field is focused, unfreezing it and dispatching the appropriate packet when the user presses the key again to send the message.

The scroll view is a bit more finicky, and relies on some included layout components to create the desired behavior. The scroll view effectively operates by dynamically repositioning a child view and clipping it at the top and bottom bounds of the parent view.

If you look up basic examples of how to use Unity scroll views, they usually focus on using a single text label as the content being scrolled. This doesn’t work well for a chat UI, despite its apparent simplicity, for two reasons: first, we need to be able to remove older messages instead of adding onto the label forever. More importantly, Unity labels do not automatically change their dimensions to fit their content when you append text, at least in a way that plays nicely with the scroll view. Plus, we’d ideally like to have some control over the margins between chat messages.

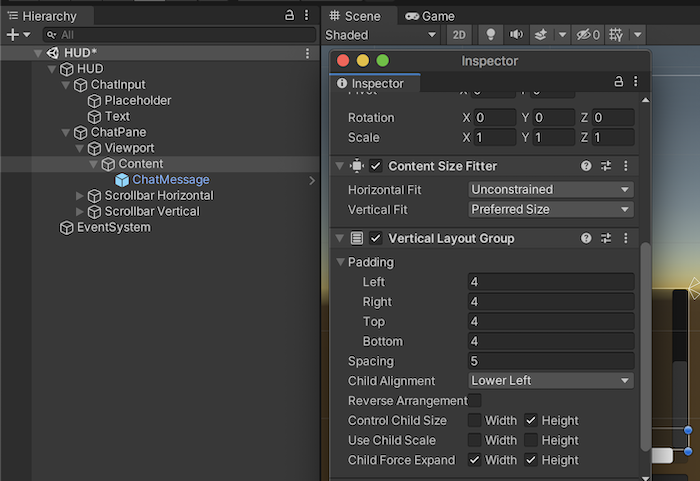

The most elegant solution is to take the Content object, a Rect, which is basically just a holder for a transform, and apply the included “Content Size Filter” and “Vertical Layout Group” components. These together will make the Rect Transform expand in a predictable way, and automatically arrange child objects that are added. It took a little bit of trial and error to get everything to play nice, but the end result is that any prefab instantiated and made a child of the Content object will be vertically stacked.

With that in place, all that’s needed is a simple prefab of a text label. Whenever a chat packet comes in, a listener in the chat pane’s MonoBehaviour instantiates the prefab, sets its parents to the Content view, and then sets the text to the string value from the network packet. The text’s paragraph style is set to wrap horizontally and overflow vertically, so the label will expand.

When instantiating the prefabs, they’re also pushed onto a queue, with the oldest dequeued when there are more than a configurable number in the queue. This keeps the scrollback from growing endlessly and becoming unmanagable.

Command Framework

The whole system revolves around a simple abstract Command class with a handful of properties that implementations set.

public abstract class Command {

public string name { get; protected set; }

public List<string> aliases;

public string description { get; protected set; }

public string usage { get; protected set; }

public PermissionLevel permission { get; protected set; }

//constructors abbreviated…

public abstract bool Execute(Client client, string[] args);

public bool HasPermission(Client client) {

return Client.role >= (int)permission;

}

}The heart of the class is the abstract Execute() method, which is overridden by any implementing class. When a command comes in, the command manager looks up the appropriate class, in its dictionary of registered commands, and invokes its Execute() method. You might recognize this as the Visitor design pattern.

Most of the properties are fairly self-explanatory, with permission being an enum of appropriate roles that command access may be limited to. The HasPermission(Client client) method exposes an easy way to verify that the issuing client has access to the command.

The aliases list allows a command to optionally provide alternate names that it may be invoked with, which are added to the command manager’s map upon registration. This way commands like /say can have short versions, such as /s.

The CommandManager is, at its simplest, a Dictionary mapping command names (or aliases) to their appropriate handler classes. A Register() method takes care of inserting the commands and making sure the aliases are added as well, and the basic commands are registered when the manager is instantiated. (However, it’s certainly possible for commands to be registered from elsewhere, perhaps in some sort of module/plugin system.)

Whenever a command packet is received, the server calls the CommandManager’s Dispatch method, supplying the Client issuing the command as well as the raw string from the packet. The function does some normalizing, ensuring the leading slash is removed and splitting the string into a command name and an array of arguments, much like we’d expect from a shell environment. The method then tries to find the appropriate command class, does a permission check, and runs the arguments through a basic sanitizing function to ensure that there are no Unity Rich Text tags. If everything checks out, the command class’s Execute method is called. otherwise, an appropriate error message is sent back in the form of a red-colored chat packet.

Basic Commands

I already implemented a few basic commands, allowing for basic chatting in the same zone or directly messaging players. The /say command illustrates the basic structure of a simple command, and is the command that is automatically sent by the client if the user does not prepend a slash to the string they enter into the chat input field.

public class SayCommand : Command {

public SayCommand() : base("say") {

usage = "/say <message>";

description = "Sends a chat message to everyone in the Zone.";

permission = PermisionLevel.DEFAULT;

aliases.add("s");

}

public override bool Execute(Client client, string[] args) {

var zone = client.player.GetZone();

var msg = string.Join(" ", args);

foreach (Player p in zone.Players) {

p.SendChatMessage($"{client.player.Name}: {msg}");

}

}

}There is also a corresponding /me command for roleplaying messages or the fine IRC tradition of trout-slapping.

Direct messages are mostly implemented as well. You can target a message to a player with a command in the form of /msg <firstname> <lastname> <msg>. Whenever you send a message to another player, or receive one, a property is set that enables the /r <msg> command to automatically reply to the correct player, keeping the conversation going without having to deal with the cumbersome name each time.