MMORPG Devlog 2: Networked Player Movement

This post is part of my MMORPG Devlog series.

It’s been a few months since my last entry, as expected. School and some medical things kept me busy for most of that time, but I finally got to work on the game a bit while isolating for the start of the new semester, and have kept at it since. Most of this round of progress happened over a three week span, and I’ll probably keep picking at it until homework levels ramp up again.

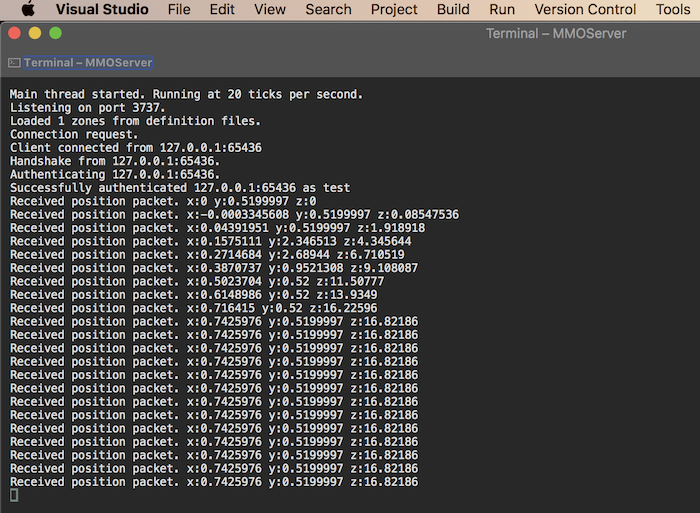

The big thing this time is synchronizing player positions and rotations over the network. It’s finally working, so I’m going to go over the major steps in getting this crucial feature up and running.

Sending Client Movement

The first order of business was picking up where I had left off: I had a working player controller, and the server could successfully instruct the client to load a zone and spawn the player prefab. So, the next step was taking the player’s movement and sending it to the server in a stream of packets.

The general plan, as I mentioned in my previous entry, is a fairly simplistic model along the lines of what you see in Minecraft or World of Warcraft. (My past experience making Bukkit plugins for Minecraft probably had an influence on my design decisions, as well as the simplicity.)

-

The client sends a packet, n times per second, containing the new position and rotation

-

The server checks the Euclidean distance between the last location and the new one. If it’s further than expected, it refuses to update the position and sends the client a reset packet that “rubber bands” the player back to the last known good position. Otherwise, the Player model’s position and rotation properties are updated.

-

If the player is stationary, the client only sends the packet once per second.

I’ve tweaked the send rate a little while working on this. Currently, I’ve settled on 5Hz, which seems sufficient for an RPG type game. It’s also fairly easy to adjust later, if necessary.

Eventually, I’ll probably add some additional anti-cheating checks…like ensuring the client doesn’t fudge the vertical component of the position in order to fly.

Broadcasting Positions to All Clients

Now that the server knows where everyone is, it needs to tell the clients.

In Untitled MMO Project, the server considers Players to be children of the Zone they are in. The overall design makes it easy enough to get the Player (or its network client object) from anywhere, but the Player’s Update() method is called from within the Zone’s Update(). This seemed like a sensible design, because it means we get some nice features for free: any player state packets, such as movement, are conveniently isolated to the only place they are relevant. If a player is AFK in a tavern on one side of the world, they don’t need to know what another player is doing in the mines somewhere else. It also means we have a convenient list of everyone in the same locale, which we probably need more often than a list of every player connected to the server.

public void Update() {

if (Players.Count > 0) {

BroadcastPlayerPositionPackets();

}

}The actual broadcast method simply iterates all clients in the zone, then sends a packet to each for every other player in the zone. It also does a check to get which server tick we’re on, out of each second, and returns early if it’s not on the list of ones that we want to send packets on. (The goal is 5Hz, not on every single tick.)

Later on, I came back to this and added some additional bandwidth-saving:

-

If a player is stationary, its position will only be broadcast once per second. (To match the client behavior.)

-

If a player is further than a certain (configurable) distance from the client being notified, the position will only be sent once per second. So, the client is notified of movement changes at the full rate when players are nearby, but if they’re far away, fewer packets will be sent. The resolution of the movement is less important at a distance, and it saves a bit of bandwidth.

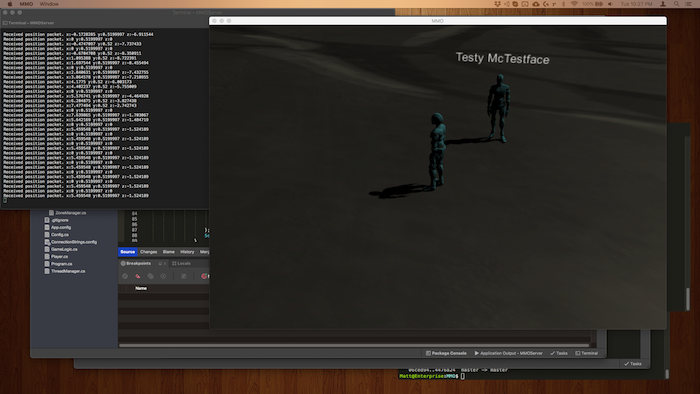

Spawning Remote Characters

Now our client can tell the server where it is and is kept up to date on where other clients are. The next step is to actually spawn player prefabs in for the other players, and update their position as packets come in. Then we can finally see the whole thing in action.

On the server side, it’s a simple matter of hooking another packet-launching method in where players enter the zone. When a player spawns, all the other clients are notified with a packet indicating that a new player has arrived, with identification and state. The client is where things get more involved.

First, I needed a Unity prefab for the character. I copied my LocalPlayer one, which uses a stock model and animations from Adobe Mixamo, and tweaked it a little before naming it RemotePlayer. The components for turning user input into movement were removed, among other things, and I added a floating TextMesh to be the name plate.

Now I can spawn it programmatically:

var path = "Player/RemotePlayerPrefab";

var obj = Instantiate(Resources.Load<GameObject>(path), loc, rot);One weird quirk of Unity’s asset management is that you can only use the Instantiate() function on assets that are inside a Resources directory. It won’t work on any others. This has something to do with the way Unity only includes assets that are physically present within a scene, to keep disk usage under control. If an asset is under Resources, it will be included regardless of being present in a scene.

With the object dynamically instantiated, I then set the TextMesh’s value. I also put a reference to the GameObject into a list in a class that deals with scene state. That way, whenever I need to iterate players and update them, I can just hit that list instead of having to traverse scene transforms…which I’m sure is much slower, as well as less convenient.

Bonus: the player’s nameplate really needs to face the camera at all times. Have you ever played a game where you have to walk in a circle around a player to see their name? That would be silly. Fortunately, it’s a simple matter of copying the camera’s rotation to the transform of the TextMesh.

// Make the nameplate face the camera

NamePlate.transform.rotation = Cam.transform.rotation;This could also be used for a DOOM-style game, where the characters are 2D sprites in a 3D world. You’d just put the flat images onto plane objects, and keep their rotation synchronized with the camera orientation.

With all that done, we’re now at a place where you can connect a second client and see it walk around.

Smoothing Out the Movement

As things stand, we have achieved networked player movement. Unfortunately, the players are just teleporting from place to place as the packets come in. At five packets per second, it’s very noticeable. And with some lag, it gets even worse.

That’s where our friend Linear Interpolation (Lerp) comes in. Getting this right was one of the most time-consuming parts of this batch of work. In principle, we want to take our current position and target position, and smoothly slide from one to the other, over a duration that is roughly in line with the time between the packets. This creates the illusion of continuous movement, and fails somewhat gracefully when the time between successfully delivered packets isn’t optimal.

Initially, I was over-engineering things. I had a queue for the packets and had tried a whole mess of different ways to calculate the t value. Eventually, I came to a much simpler solution that works without all of the mess: store the latest packet and the time (frame count) it was received, as well as the pair from the prior packet.

float duration = thisPacketTime - lastPacketTime;

float t = Mathf.Clamp01((Time.frameCount - packetTime) / duration);

Vector3 pos = Vector3.Lerp(prevPosition, targetPosition, t);It seems to work nicely so far. With the animations turned on through a couple of calls to the Animator component, it all comes together.

Note that the motion may look a bit choppy due to this being a GIF.