MMORPG Devlog 4: Pathfinding and Server Side Geometry

This post is part of my MMORPG Devlog series.

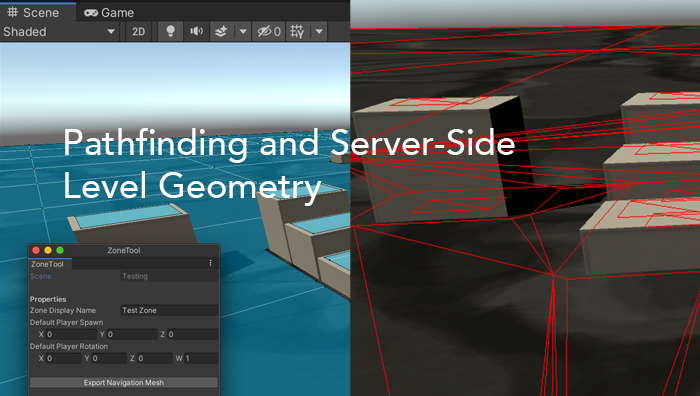

Way back in my first devlog post, I talked about designing the Zone architecture. I sketched out the basic server-side concept of an area in the game, with an associated Unity scene and set of players (and eventually Entities like monsters and Non Player Characters). This involved creating a basic exporter to turn the Unity navmesh into an OBJ file, with the end goal of having the basic level geometry on the server, for pathfinding and validation of some player behaviors.

I expected this to be a very involved part of the project, as well as a vital one, but I was surprised to find that there were precious few resources online that even talked about the implementation of navmeshes. You can find lots of pages about using the Unity and Unreal navmesh tools, and things about Valve’s usage of square-based ones in their games, but there are very few articles that discuss their implementation at a theoretical level. So, I had a lot to figure out on my own.

What Exactly is a Navmesh?

A navigation mesh is a simplified form of a video game level, consisting of a single 3D model that represents the places where a character can walk. Basically, it’s your ground, with holes where obstacles would be. This is used with a pathfinding algorithm to allow an NPC to find the shortest path from one coordinate to another, making it a core part of game AI.

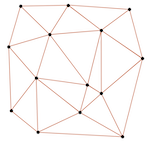

Navmeshes are made up of convex polygons, triangles typically, that tesselate to form the surface. Since we mostly experience 3D models in a more or less tangible form, as characters and environments in movies and games, we’re kind of conditioned to think of them as physical objects. However, what they boil down to is simply a list of vertices and the edges connecting them. In fact, that’s exactly how the OBJ file format works: it’s a text-based list of vertex coordinates and a list of vertex triplets that form triangles. When you draw out all of those points and connect them, you get something that looks like a thing.

Where am I going with this? So, we have a bunch of vertices connected by lines. Doesn’t that sound like a different concept that always comes back to haunt Computer Science types? That’s right, graphs. Yep, computer graphics are an expression of mathematical graphs. Whenever a game engine displays a model, it’s just taking a list of points and their relationships and telling the graphics context to draw lines between them. So, if we have a graph, then we know exactly what sort of data structures we can use to hold the data on the server…and we know we can use graph searching algorithms to do pathfinding. Dijkstra, Astar, Depth First Search…we just need to parse the OBJ file into any basic representation of a graph, and then we can traverse it.

Visual Debugging

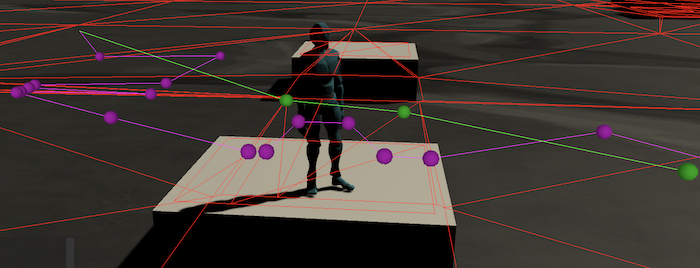

Before diving into this, I wanted to make sure I had a way to visualize what the server was doing, for debugging purposes. So, I made a new network packet that holds six numbers: the x, y and z coordinates for two points in a line. With the server able to send that, I wrote up a couple of quick functions allowing the client to receive these and add them to a list, drawing them on-screen in the Unity Editor with the “gizmo” feature.

By simply invoking Gizmos.DrawLine(from, to) for each received set, I could have the server draw arbitrary red lines on the client’s screen when the game was run from within Unity. And if you can draw a line, you can draw three lines and make a triangle. Armed with that little quality of life feature, I’d be able to more confidently work on the server side.

Putting Level Geometry on the Server

The Wavefront OBJ format that I use to hold the exported navmesh generated by Unity is very simple in concept. It uses plain text to produce a list of coordinates representing the vertices, and then connects them with a list of triangles that reference the vertices ordinally. Parsing it is then just a matter of string wrangling.

# vertices

v -76 0.55 -102

v -51 0.55 -102

v -51 0.55 -128

...

# triangles

f 1 2 3

...My goal here was to turn the OBJ file into an in-memory list of triangles, a List<NavMeshTriangle> property in my navmesh class. The triangle class would hold three vectors, each representing a vertex in the triangle.

public class NavMeshTriangle {

public Vector3 A { get; }

public Vector3 B { get; }

public Vector3 C { get; }

// simplified, omitting some helper methods and properties introduced later...

}The resulting algorithm is surprisingly simple. You load the file and read it line by line, doing the following:

-

If the first character is a

v, split the line on the space character and make a new Vector3 out of the three numbers. Add the Vector3 to a list of vertices. -

If the first character is an

f, split the line on the space character. Then look up each of the vertex IDs (indexed starting with 1) in the vertex list. i.e.vertices[id1 - 1]. Then construct a new triangle object with the three Vector3s we now have and add it to the triangle list. -

Else, this is probably a blank line or a comment, so just ignore the line and continue the loop.

Now if I loop through my triangles, and send those debugging packets I made earlier, drawing A→B, B→C, C→A, I can see my navmesh drawn out in the Unity scene!

On the software architecture side, I did a little bit of planning for the future as well. My NavMeshTerrain class is implementing an interface called ITerrain. The Zone class then has a property ITerrain Terrain to hold the level geometry. I plan to have some zones be procedurally generated, changing from time to time, and those zones may use a completely different sort of data to represent the level geometry. For example, a heightmap generated by the server. So, I created a contract of methods that a terrain must have, and then various terrain types implement those.

public class ITerrain {

bool PointOnTerrain(Vector3 point);

List<Vector3> FindPath(Vector3 from, Vector3 to);

}Those are two of the main things we want to do with our terrain: tell if a point is traversable or not (i.e. it exists within a triangle in the list) and run a pathfinding algorithm. In order to do either, there’s still more work to do…

Finding the Triangle for a Point

One thing we will need to do frequently is determine whether a given point is traversable or not. Maybe we want to see if the player is standing in a valid location, or if there’s an obstacle preventing some sort of action. Determining traversability on a navmesh more or less means “does this point exist within the bounds of one of the triangles.” Since we have a list of triangles, this means iterating it and performing a geometric algorithm on each one. We will also need to do this as a part of our pathfinding, so we can determine which triangles the start and end coordinates are within.

What we’re trying to do is a “point in triangle test.” There’s an easy approach in the linked page, as well as a faster but more complicated Barycentric technique. There is also a page on the Unity wiki that shows a C# implementation of this test.

Leaning on those resources, I put together a function to determine which triangle, if any, a point is inside, and then wrapped that to implement the PointOnTerrain(...) method.

Connecting the Triangles

You may have noticed that we still don’t have a graph. We have a list of unrelated triangles, which is decidedly not a graph. This list is convenient for searching for a specific triangle, but we need to connect them up to be able to do pathfinding and such. Each triangle object in the list gets a list of neighboring triangles: an Adjacency List.

public class NavMeshTriangle {

public Vector3 A { get; }

public Vector3 B { get; }

public Vector3 C { get; }

public List<NavMeshTriangle> Neighbors { get; }

}By prepopulating the adjacency lists when the OBJ file is parsed, we create a data structure that is nice and fast to walk through for pathfinding purposes. With a starting object in hand, you already have the neighbors and those have their neighbors, and you can recursively run through them without doing any further geometric calculations.

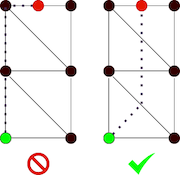

But why are we even storing full triangles and trying to determine adjacency? Why not just connect the vertices up with the edges the OBJ file defines, and pathfind on those directly? That’s certainly possible, but the resulting behavior would cause characters to hug walls or take strange back-and-forth paths. The approach I’m going for is to connect the centers of the triangles in a graph and have the character walk from the triangle to the closest point on the shared side of the next triangle, so they walk more naturally.

The function that I wrote to preprocess all of the adjacency lists isn’t the most efficient—it has an apparent time complexity of —but it only runs once on server startup, so I’m willing to leave it be for now instead of prematurely optimizing. If it turns out to be too slow on zones with a higher polygon count, I can certainly improve upon it.

foreach (NavMeshTriangle tri in Triangles) {

foreach (NavMeshTriangle t in Triangles) {

byte shared = 0;

if (VEQ(tri.A, t.A) && VEQ(tri.B, t.B) && VEQ(tri.C, t.C)) continue;

if (VEQ(tri.A, t.A) || VEQ(tri.A, t.B) || VEQ(tri.A, t.C)) shared++;

if (VEQ(tri.B, t.A) || VEQ(tri.B, t.B) || VEQ(tri.B, t.C)) shared++;

if (VEQ(tri.C, t.A) || VEQ(tri.C, t.B) || VEQ(tri.C, t.C)) shared++;

if (shared > 1) tri.Neighbors.Add(t);

}

}It looks a little messy, but all it’s doing is looping through each triangle and then checking every other triangle to see if it shares two vertices. A triangle that shares two vertices with another triangle must share a side, so it gets added to the Neighbors list.

The VEQ() function tests the equality of Vector3s, as they’re a floating point numbers, which don’t compare cleanly. The server is a .NET Core application using the System.Numerics vectors. Unity might have some tricks up its sleeves for comparing vectors, but Microsoft’s Vector3 implementation will not always equate two vectors even if they should be the same. So, I’m just checking if Vector3.DistanceSquared(a, b) < 0.001.

Now we have a graph.

Pathfinding with A*

With a graph in hand, the overall problem of finding a path from Point A to Point B has become one of the classical Computer Science problems: searching a graph to find the shortest path. This may also bring up unpleasant memories for those of us who sat through Data Structures and Algorithms classes, especially when dropping terms like “Dijkstra’s Algorithm” or the infamous CLRS Introduction to Algorithms textbook…

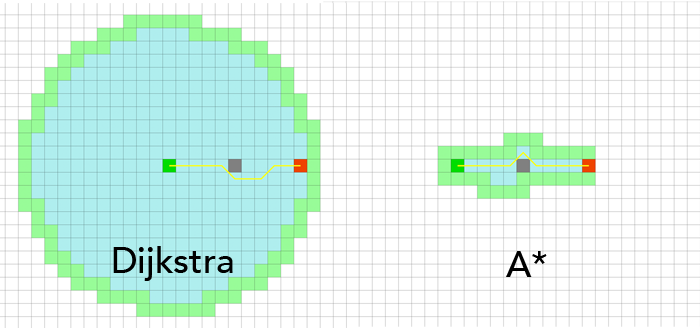

The A* algorithm is potentially the most popular pathfinding algorithm used for games, because it doesn’t have a lot of moving parts and it’s relatively fast. Developed for a robotics application, it’s more or less an extension of Dijkstra’s famous pathfinding algorithm, but with a heuristic function that “aims” the search to avoid processing nodes that are not vaguely in the direction of the target. While Dijkstra has to search every node in the graph to evaluate the shortest path, A* will run straight toward it and eliminate nodes that aren’t going to get it anywhere.

In each iteration of the algorithm’s main loop, it estimates the cost of the path and tries to minimize the increase of the cost function, which is defined as , where is the cost of the path from the starting node and is the heuristic function, which estimates what the optimal path’s cost “should” be.

Since my graph is inherently made up of geometry, and I already have objects that hold this information for me, I can use the actual distance between the triangles’ center points for my cost functions. First, I needed a helper function to determine the Euclidean distance between two triangles’ centers. (The DistanceSquared(...) method is used to avoid a slow square root operation when calculating the length of a vector.)

private int AstarDist(NavMeshTriangle a, NavMeshTriangle b) {

return Convert.ToInt32(

Vector3.DistanceSquared(a.CenterPoint(), b.CenterPoint())

);

}I had already defined a CenterPoint() method on the triangle class, which is simply the triangle centroid formula of . So now I can define my function as AstarDist(target, n), as AstarDist(start, n) and as the sum of the other two.

The overview of the A* algorithm is as follows.

While the open set is not empty:

- Set the current node to the one in the open set with the lowest cost.

- Add the current node to the closed set and remove it from the open set.

- If the current node is the target node, prepare the path and return it.

- For every neighbor in the current node:

- Skip the iteration if the current node is in the closed set.

- If or if the neighbor is not in the open set: store the fact that we came from the current node to get to the neighbor node. If the open set does not contain the neighbor node, add it.

The “came from” part is often referred to as “parenting” one node to the other, and is how you walk through and produce a path after the algorithm is done. Often this is done by actually putting a “parent” property on the nodes, but I intentionally chose to not mutate the nodes. Instead, I have a dictionary called cameFrom that uses a triangle node as the key, and another as its value. When we reach the condition in step three, where the current node is the target node, I start with the target node and do this:

var path = new List<NavMeshTriangle>();

var n = end;

while (n != start) {

path.Add(n);

n = cameFrom[n]; //set the next n to the parent node

}

path.Reverse();

return path;That way I keep the NavMeshTriangle unchanged because this operation will be run frequently and keeping state out of the geometry objects will be important.

Another consideration is the type of data structures used for the sets. The open set is a List (backed by an array in C#), because we need to address nodes by index in the main loop, but the closed set is a HashSet. closedSet.contains(...) is called three times in the neighbor-checking loop, while we never call that method on the open set, so optimizing it by using a proper set structure is sensible.

All in all, A* is fairly straightforward to implement if you have some familiarity with graph traversal, and there are tons of examples online in every imaginable language. It’s mostly just a case of tweaking the basics for your use case and graph implementation.

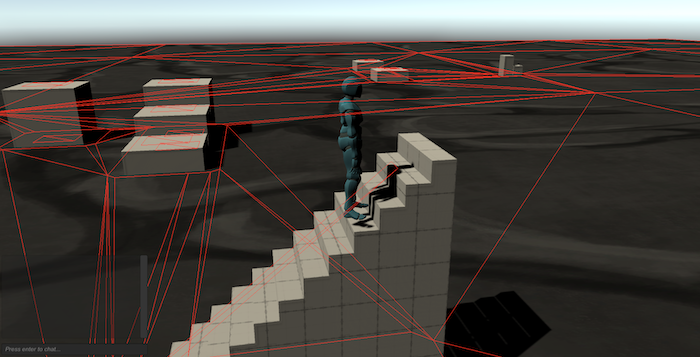

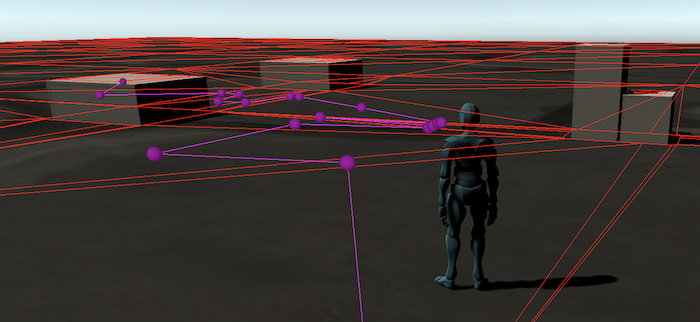

With all of that done, we can now find paths between two points!

As you can see in the above image, the path looks a bit too zig-zaggy. What we’ve done so far is to generate a coarse path, using the triangles on the mesh as our pathfinding nodes. However, walking from center-to-center is a bit awkward, obviously. Now that we have the collection of triangles to pass through, we can look at refining the path by walking to the closest point on each shared edge, producing a straighter path. However, there’s a slight detour to be made first…

Raycasting to Improve Triangle Searching

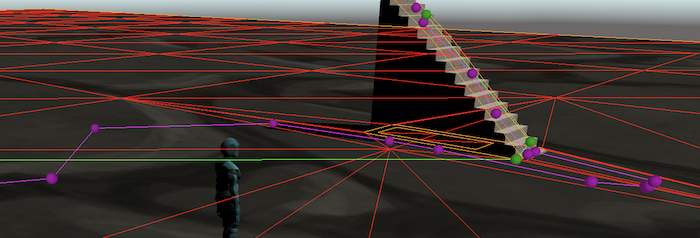

In testing the pathfinding, I noticed that the whole thing doesn’t work if the coordinate used is not precisely on the same plane as the triangle being searched. While this works just fine on our ground level, if I try to pathfind up the stairs, the coordinates are not going to line up, since the player model doesn’t stand perfectly on top of the stair mesh. So instead of checking triangles with just the point-in-triangle test, I’m going to have to do some raycasting.

Finding the point where a ray cast out from an origin hits a triangle is a well-tread problem, one that is core to computer graphics. The basic idea is to produce a plane from the points on the triangle (a surface that has an orientation but extends to infinity on each side) and figure out the point where a ray (origin point and direction) intersects the plane. Then that point can be fed to the same point-in-triangle function to establish whether the raycast hit is within the triangle or not.

After hacking at it myself for a few hours, I found an excellent article that provides a more thorough explanation of the solution and a more succinct approach to implementing it. I ended up adapting their approach to finding the intersection point on the plane, and then fed that to my existing point-in-triangle test.

private bool RayHitsTriangle(Vector3 rayPos, Vector3 rayDir, NavMeshTriangle tri) {

float normalDotRayDir = Vector3.Dot(tri.Normal, rayDir);

if (MathF.Abs(normalDotRayDir) < Double.Epsilon) return false; //parallel

float d = Vector3.Dot(tri.Normal, tri.A);

float t = -(Vector3.Dot(tri.Normal, rayPos) - d) / normalDotRayDir;

if (t < 0) return false; //triangle behind ray

Vector3 point = rayPos + t * rayDir; //plane intersection point

return PointInsideTriangle(tri, point);

}I also updated my triangle class again. I already had a Normal() method that would return a vector for the triangle’s surface normal (cross product of two edge vectors), but I ended up caching that as a property when the object is instantiated. I also added an Area property at the same time (length of the normal vector).

Now to actually use the new function: when searching for a triangle by a point, I call RayHitsTriangle(...) with the desired point, but with a y value two units higher, and a downward ray direction of Vector3(0, -1, 0).

With that finished, paths are now working properly at different heights and angles.

Now we can get back to making the path less zig-zaggy.

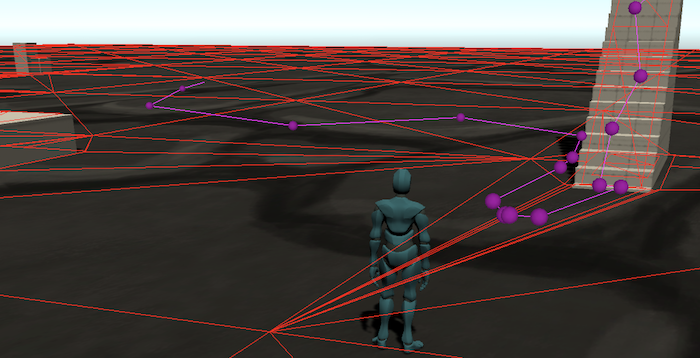

Refining the Triangle Path with Edge-to-Edge Movement

While the A* algorithm is finding a path through our triangle nodes, we don’t actually want to walk to the center of each triangle. The triangles vary in size, and can be quite large, so walking to the center can often mean taking quite a long walk out of your way. What we really want is to walk to the nearest point on the shared edge of two triangles.

This basically works by finding the shared edge (two identical points shared between a triangle and the next) and finding the nearest point along it, treating it as a line segment. This is how I ended up approaching it:

var dir = point - segmentA;

var lineSegment = segmentB - segmentA;

float t = Vector3.Dot(dir, lineSegment) / lineSegment.LengthSquared();

var intersection = segmentA + (t * lineSegment);The t variable ends up being a fraction of the line segment’s length, which is multiplied against the line segment magnitude to get the final point. It seems to work all right. As you can see below, it is already straightening the path out quite a bit.

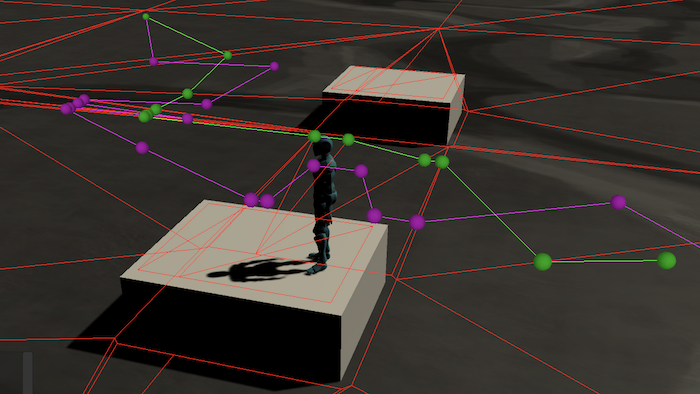

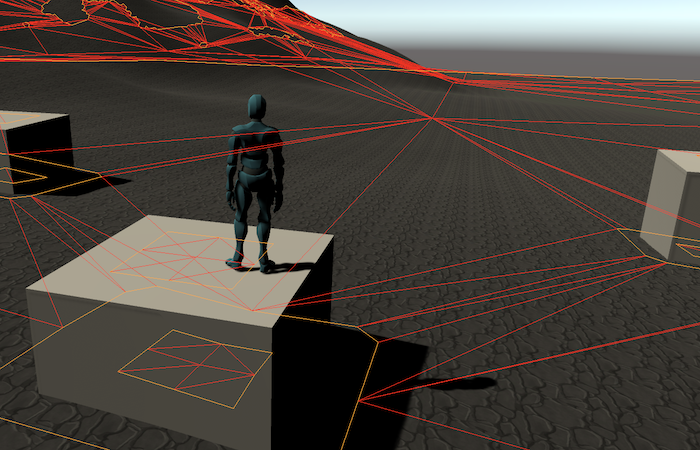

Now, there are still more points than we really need, and the path could still be a lot straighter. If you have a line of sight to your destination, you really want to just walk in a straight line. So, I put together a simple pruning algorithm that iterates the points and does a line of sight check on each subsequent point, only adding points to the pruned path if the line of sight check fails.

The line of sight check is testing for the intersection of two line segments, one representing a line between the two path points and the other being a triangle edge that is “obstacle.” An edge is an obstacle edge if it is not shared with another triangle.

With that change in place, it’s looking just about perfect.

Another minor refinement I made in the FindPath(...) wrapper method is to skip pathfinding altogether if the starting and destination points reside in the same triangle, because then you can just go in a straight line.

After about four weeks of working on pathfinding, I think it’s finally in a state where I’m happy with it for now. Since I knew it was going to be one of the more complicated parts of this project, I wanted to make sure I got it done over the summer before I had classes to distract me again.

Of course, there is still some more to be done on server-side geometry issues. I did think to test the pathfinding with a scene that features a one square kilometer terrain object, with some quick mountains and such painted on. It worked fine, after a little bit of debugging to smooth out some minor glitches with the raycasting and a bug or two with the player spawning in a new zone, but there are some definite performance issues to address.

A larger zone with a ground that isn’t simply a plane ends up having many more triangles (the navmesh Unity generated has several thousand) and this is noticeably slow for pathfinding…as well as taking several seconds to generate the neighbor properties on the triangle objects. Again, that latter one isn’t the end of the world (but it would be nice to improve upon). However, it’s important that the actual pathfinding process be reasonably fast, so further investigation on that front is necessary.

Edit: After some investigation, it turns out that the apparent sluggishness is a result of the debugging tool drawing too many gizmo lines on the client. The pathfinding is actually lightning fast.

Beyond performance, a later step will probably be to implement some functionality for placing Unity’s colliders on the server as well, so we can do raycast tests to see if enemies can see a player or if a player has line-of-sight to shoot a spell. My as-of-yet undeveloped plan is to build another exporter that will read the colliders’ shape and dimensions and produce another OBJ file for these static objects. Then the server can import that file and use the geometry for simple raycast tests.

Back to Chat: Tab Completion and Teleportation Commands

Before starting this major endeavor, I finished up some loose ends for the chat and command system. Most notably, I implemented a simple autocomplete system for player names and subcommands. Typing out a player’s full name is tedious, especially when direct messaging several players, and it would definitely be nice to avoid that. So, by default, if you type out a few letters and press tab, the game will autocomplete to the first online player that matches. In addition to this functionality, each command has the opportunity to override a TabComplete() method from the superclass, so completions can be applied to things like subcommands as well. Basically, it works like a simplistic version of the completion you get in a shell like Bash.

When the user presses the tab key, a packet is sent to the server with a string containing all of the text to the left of the insertion point. The server looks up the command (which might just be /say) and invokes its TabComplete() method, whether it’s explicitly defined by the command or the player name one inherited from the base Command class. This involves some string-wrangling, and then function spits out the completion text and we can get back to the fun part.

The server eventually sends this packet back to the client:

public class ChatTabCompleteResponsePacket {

public string originalText { get; set; }

public int start { get; set; }

public string replacement { get; set; }

}We’ve got the original text the client sent in its request packet, a starting index that defines where in the string the replacement begins, and the text to replace. Then it’s a simple matter of doing a Substring() replacement on the input field’s text object and then moving the caret to the new end of the string.

public class ChatTabCompleteResponsePacket {

ChatField.text = ChatField.text.Substring(0, packet.start) + packet.replacement;

ChatField.caretPosition = ChatField.text.Length;

}I also added some basic teleportation commands for debugging and moderation tasks. A /tpzone command moves the player from one zone to another, and a /tp command allows you to move yourself or another player to specified coordinates within the current zone. Mostly I’m using these to move clients around for testing purposes, and as a way to verify that my permissions scheme works correctly, but they could potentially be used in a live game to unstick players or for moderators to more easily move between areas to observe. (In a similar vein, I also implemented a /kick command that boots the named character from the server.)

Minor Bug Fixes

- Properly despawn characters on the client when the relevant packet is received.

- Properly despawn players from the server when their clients disconnect.

- Return to the login menu when the connection to the server times out.

- Fixed an issue where the chat input would be unexpectedly focused.